The ruling elite is the central actor of the state. From this, it follows that the direction of state action is defined by the ruling elite’s actions, grounded in certain motivations of rulership. Distinguishing ideal type motivations, we can define subtypes of the state, each of which is led by a ruling elite running on a specific motivation. Naturally, political actors of a regime can have various goals, but we can—at least for the purposes of our definitions—identify general, overarching principles, some pursued value or common interests, which bind the ruling elite together. More precisely, as certain elite factions may even contradict the acts of other public actors or factions, what we define are not simply general but dominant principles, that is, the one that fits to most actions of the state (the ruling elite). This is what we call the dominant principle of state functioning. Defining state subtypes, the role of the dominant principle can be understood as if it was the ruling elite’s “constitution,” meaning the fundamental character of their behavior can be derived from it, and therefore also the fundamental features of their states, which their actions define (as central actors).

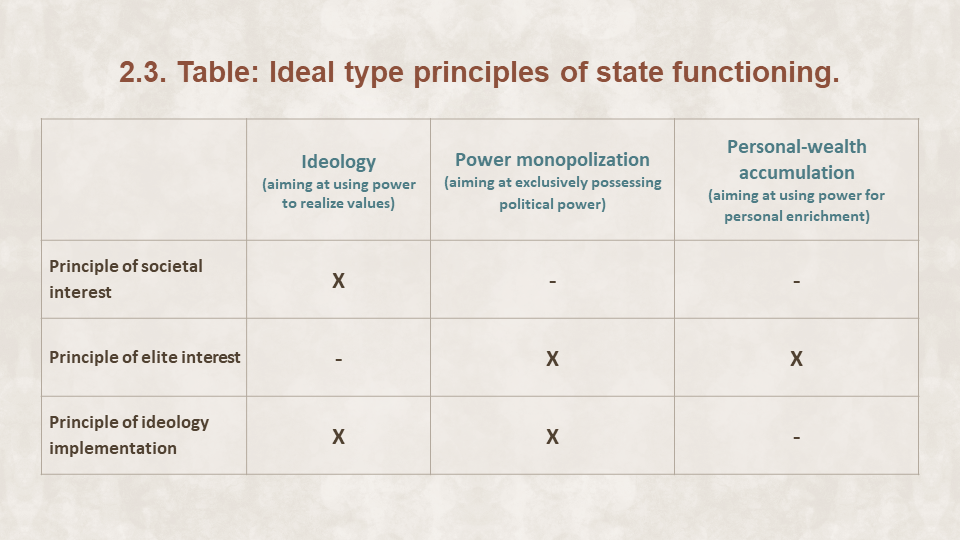

There are three ideal type principles we define as the combinations of certain features (Table 2.3). First, there is the principle of societal interest:

- Principle of societal interest is a dominant principle of state functioning, where the ruling elite aims at using political power to realize values (an ideology) but does not aim at exclusively possessing it (no power monopolization). In this principle, the ruling elite focuses on societal groups outside of the political sphere and state action manifests dominantly in enhancing the interests of such groups (their wealth, power, liberty etc.).

For the sake of practicality, we define “interest” in this context as the provision and enhancement of what philosopher John Rawls puts in the category of primary goods, which every man can be presumed to have an interest in. These include income and wealth, physical security, basic rights and liberties, the powers of offices and positions of responsibility etc.[1] The “societal interest” means (1) the provision of basic rights and liberties for the entire population and (2) serving the material interest of some social groups outside the ruling elite (that is, non-political societal groups: economic classes etc.) which the rulers decide to prioritize through the state. In other words, societal interest consists of the particular interests of certain groups of society. Which groups are to be prioritized is defined by the respective actors’ ideology, which we simply define as a belief-system voiced by political actors about the proper functioning of society [→ 6.4]. Putting them together, we claim that where the dominant motivation of the ruling elite is to realize an ideology but it does not try to possess power exclusively, that means it operates the state by the principle societal interest. For (1) the lack of exclusive possession of power means pluralism, and from the acceptance of pluralism (i.e., the lack of aiming at exclusivity) the provision of basic rights and liberties for the whole population follows [→ 4.2.2], and (2) an ideology entails a vision about the proper functioning of society, from which certain state actions follow which prioritize social groups outside the ruling elite [→ 4.3.4.1].

The second ideal type principle is the principle of elite interest:

- Principle of elite interest is a dominant principle of state functioning, where the ruling elite aims at exclusively possessing political power (power monopolization) and using it for personal enrichment (personal-wealth accumulation). In this principle, the ruling elite focuses on itself, that is, the political sphere, and state action manifests dominantly in enhancing the interests of the rulers (their wealth, power, liberty etc.).

The dichotomy of societal and elite interest has been present in political science since Aristotle.[2] In a more recent work, North distinguishes in existing literature the “contract theory” of state, where “the state plays the role of wealth maximizer for society,” and the “predatory theory” of state, where the state maximizes “the revenue of the group in power.”[3] In our understanding, the elite interest is served and the state runs on the principle of elite interest when:

- the ruling elite tries to exclusively possess political power (power monopolization and centralization), involving (a) the extension of formal and informal influence over the political sphere, and (b) ensuring unchallengeability, breaking autonomy and/or power of competing actors so they cannot hinder the leader in exercising political power;

- the ruling elite uses the unconstrained power to enhance its wealth (personal-wealth accumulation), involving (a) enriching themselves, or in the case of patronal autocracies the members of the adopted political family, and (b) enriching those who can be vassalized, that is, with whom the ruling elite (and especially its top leader) can establish a lasting patronal relationship of dependence.

It needs to be seen that power monopolization and personal-wealth accumulation are twin motives: they can hardly be separated or even put in a hierarchical order. For power is necessary to accumulate wealth [→ 5.3.2] and wealth is put in use to maintain power [→ 5.3.4.4]. No wonder the Russian literature speaks about power&ownership (vlast&sobstvenost), referring to the fact that, in the post-communist region, there is no power without ownership and there is no ownership without power.[4] The two go hand in hand, and the two cannot be separated in short of a non-wealth accumulation focused ideological program. Moreover, such a ruling elite can be described as not ideology-driven but ideology-applying [→ 6.4.2]. It might communicate an ideology, a vision about the proper functioning of society, but the actions of the state cannot be derived from it. Therefore, we cannot treat the communicated ideology as the dominant principle of state functioning.[5] Rather, the actions of a state with such a ruling elite can be explained by a focus on itself, using the instruments of public authority to serve this single particular interest. In a state subordinated to the principle of elite interest, the ruling elite abuses political power for its private gain [→ 5.3] and tries to eliminate pluralism in order to preserve its monopoly of political power [→ 4.4.3].

Although we are going to elaborate on this issue in Chapter 6, it is important to stress at this point that, for us, the ideology-driven nature of a ruling elite is not a psychological issue but a sociological issue. Our claim that a system is ideology-applying does not mean that the rulers do not “believe” in what they say—a claim that could hardly be verified, given we cannot get into the rulers’ heads.[6] What we do claim, however, is that a system is ideology-driven only when an ideology fulfills the definition of a dominant principle—that is, that the main features of the state can be derived from it. As we will see, there are states where this criterion is fulfilled by an ideology, like communist dictatorship, where the main features of the regime follow from the basic tenets of the ideology of Marxism-Leninism [→ 4.2-3, 5.5.1]. But the main features of states subordinated to the principle of elite interest do not follow from the ideology they communicate, therefore we—again, from the point of view of descriptive sociology—cannot treat them as ideology-driven but only ideology-applying.

Indeed, when one tries to interpret the ruling elite’s actions by the ideology it communicates, he is no less biased than one who tries to interpret it by a supposed elite interest. Both standpoints are based on presumption: the former one’s presumption is that the given elite tries to implement an ideology (to serve the “common good”), while the latter one’s, that the elite wants to accumulate power and wealth (to serve their own private good). Which presumption is deemed “genuine” or “malicious” is irrelevant, as we are working with positive and not normative terms [→ Introduction]. What is relevant is which presumption is justifiable. If a ruling elite that dominantly accumulates wealth and power, or a state can be best approached by an ideal type based on elite interest (e.g., the mafia state [→ 2.4.5]), then presumes the principle of elite interest is justified, whereas the standpoint that accepts the ideological goals (and constantly explains that the state “makes policy mistakes” as it actually “deviates” from the goals) is unjustified. However, if the ruling elite dominantly focuses on the society and tries to reform it along the lines of an ideology, we can presume the principle of ideology implementation:

- Principle of ideology implementation is a dominant principle of state functioning, where the ruling elite aims at exclusively possessing political power (power monopolization) and using it to realize values (an ideology). In this principle, the ruling elite focuses on societal groups outside of the political sphere but state action does not manifest in serving the societal interest.

While both involve ideology-driven ruling elites, the principle of ideology implementation is not the same as the principle of societal interest because it does not secure the basic rights and liberties of the people.[7] More precisely, the particularity of the principle of societal interest is that the content of societal interest (that is, which particular interests are to be served by the state) is decided in an open, transparent and formalized process of public deliberation and negotiation, involving every interested group of the society [→ 4.3]. In other words, under this principle what is enforced is the self-defined societal interest, reached as a result of the competition of various (particular) interests of the groups of society. The role of the state is to provide a neutral framework for the reconciliation of interests [→ 4.2.2]. On the other hand, in the principle of ideology implementation the direction of state action is arrived at in a closed, non-transparent and sometimes informal, process of centralized decision-making. Thus, under this principle what is defined is a kind of postulated interest, reached as a result of the internal decisions of the ruling elite and the subjects of which are withdrawn from the scope of disputable issues. The role of the state in this model is to define the interest of the people, to which it uses an ideological framework prescribing the rulers’ vision about the proper functioning of society. This vision as well as the society’s postulated interest is then forced on the people through the state, which gives them no say in how their life is governed [→ 4.3].

Every principle of state functioning entails a specific relationship between the public sphere—the rulers and the apparatus of the state—and private sphere—the rest of the society. In states which run on the principle of societal interest, we can see a transparent/regulated cooperation and connection between the two spheres, which should always result in a conciliatory decision for the concerned groups. As under this principle public officials are expected to put societal interest ahead of their own (elite) interests, we can speak about a conflict of interests between those in the public and the private sphere. In the principle of elite interest, it is the non-transparent and informal collusion of public and private spheres that can be observed, bringing about a fusion of public and private interests. Finally, when it comes to ideology implementation the private sphere gets subordinated to the public sphere, for the former has no word in the decisions made and implemented by the latter. This can also be termed as a repression of private interests, that is, the private sphere itself [→ 5.3.5].

[1] Rawls, Justice as Fairness, 58–59.

[2] “[Men], even when they do not require one another’s help, desire to live together; not but that they are also brought together by their common interests in proportion as they severally attain to any measure of well-being. This is certainly the chief end, both of individuals and of states. […] The conclusion is evident: governments which have a regard to the common interest are constituted in accordance with strict principles of justice, and are therefore true forms; but those which regard only the interest of the rulers are all defective and perverted forms.” Aristotle, Politics, 60.

[3] North, Structure and Change in Economic History, 22.

[4] Ryabov, “The Institution of Power&Ownership in the Former U.S.S.R.”

[5] Madlovics, “A maffiaállam paravánjai.”

[6] Madlovics, 317–21.

[7] Some dictatorships in the 20th-21st centuries have shown that they can enhance the material well-being of the people, though not as efficiently as democracies and without serving societal interest in terms of basic liberties. See Acemoğlu and Robinson, Why Nations Fail.