Using the above-defined principles, we can define ideal type states of the polar type regimes, as well as start organizing the state concepts that have been used in the literature with great variation.[1] In a liberal democracy, the ideal typical state may be called a “constitutional state,” following the German notion of Rechtstaat:[2]

- Constitutional state is a state that is subordinated to the principle of societal interest and is led by a constrained political elite, its primary constraint being the separation of branches of power and the liberty and autonomy of societal groups, guaranteed by the constitution.

This definition is inspired by the mainstream understanding of constitutionalism and the rule of law, on the one hand [→ 4.4.1.1], and by the Madisonian theory of competing factions controlling each other, on the other hand [→ 4.4.1.2]. Furthermore, the definition incorporates the idea of separation of powers, that is, the constitutional separation of the executive, legislative, and judicial branches [→ 4.4.1.1].

In contrast, we can observe a merger of powers in a communist dictatorship where all branches are formally subordinated to the Marxist-Leninist state party [→ 3.3.8]. Accordingly, the state in a communist setting can be called a “party state.”

- Party state is a state that is subordinated to the principle of ideology implementation and is led by the party of the ruling elite that is completely interwoven with the state. A party state is totalitarian, which means that (1) no other components of the regime have autonomy and (2) its rulers are not constrained by other components.

In general, we can say that the principle of societal interest is associated with democracies, whereas the principle of ideology implementation is associated with dictatorships. Indeed, it is one of the main features of dictatorships vis-à-vis democracies that the monopoly of political power is held by a single entity (party etc.) that cannot be challenged; that is, the basic rights and liberties of the people are suppressed [→ 1.6].

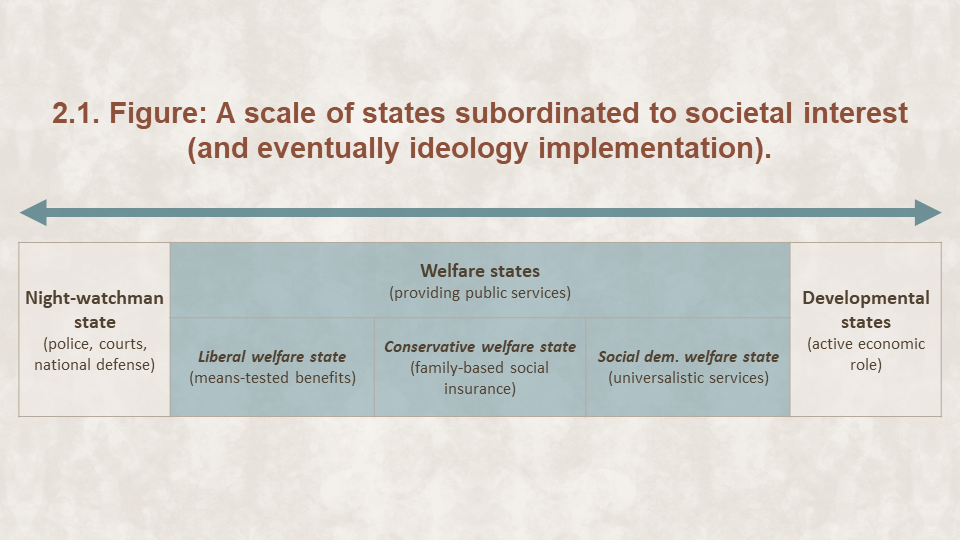

Yet both constitutional state and party state are rather broad concepts, because they do not specify precisely which ideologies the ruling elites follow. Focusing on this aspect, that is, the types of public policies [→ 4.3.4.1] these states undertake, we can define several subtypes of states that prevail among democracies and dictatorships. Using the concepts which refer to such states in existing literature, we can put up a scale from states that perform only the fundamental functions of police, courts, and national defense—that is, the so-called night-watchman state—through states which provide services such as public education and social benefits—that is, the various types of welfare states—to states which take part as entrepreneurs in the economy and play a dominant role in the realization of the communal goal of progress—that is, developmental states [→ 2.6].[3] Indeed, the night-watchman state has less empirical relevance and serves as a theoretical device to extend our scale, as most democracies in today’s world are welfare states. However, as we move from states closer to the night-watchman endpoint toward the developmental-state endpoint, and the state takes over more and more social functions, we can observe that the aim of exclusively possessing political power emerges among ruling elites.[4] Thus, at the end of the scale, the principle of state functioning tends to be ideology-implementation rather than societal interest.

A continuous scale of the above-mentioned state concepts is depicted on Figure 2.1, utilizing the paradigmatic distinction of three ideal typical models of welfare states by Gøsta Esping-Andersen.[5] It may be objected that this typology is an obsolete one, and several other typologies have been developed for welfare states since Esping-Andersen.[6] Also, because the issue of state intervention is a primary question of economic disputes, several typologies use the language of economics and find “varieties of capitalism” and neoliberalism instead of a variety of state [→ 5.6].[7] Without a doubt, a systemic analysis and refinement of these categories would be a fruitful exercise. However, at this point we refer back to the stubborn-structures argument, which stated that the two main rulership structures that can be noticed in post-communist regimes are patrimonialization and informal patronal networks. This implies that, in our view, post-communist states can be best described by presuming the principle of elite interest. Therefore, we do not expound further on the typologies based on the principle of societal interest but go on with the labels that have been developed in the elite interest paradigm.

[1] Indeed, there are state concepts that cannot be interpreted as reflecting on a feature of rulership, such as the concept of “petro state” which is used for states with many natural resources. Indeed, that concept refers not to a regime-specific but to a country-specific feature, and we are going to elaborate on those only in a later chapter [→ 7.4].

[2] For a meta-analysis, see Tamanaha, On the Rule of Law, 114–26.

[3] Johnson, “The Developmental State: Odyssey of a Concept.”

[4] Holcombe, Political Capitalism, 2018, 20–43.

[5] Esping-Andersen, The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism.

[6] For a meta-analysis, see Arts and Gelissen, “Models of the Welfare State.”

[7] The fundamental work is Hall and Soskice, Varieties of Capitalism. For later works in this paradigm focusing on the post-communist region, see Lane and Myant, Varieties of Capitalism in Post-Communist Countries; Bohle and Greskovits, Capitalist Diversity on Europe’s Periphery; Szelényi and Mihályi, Varieties of Post-Communist Capitalism.